History

“A scientist himself, he recognized that the American people must understand science.”

These were the words the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel used in 1949 to describe John Motley Morehead III and his motivation for giving his alma mater the first planetarium on a university campus. Morehead – who had discovered acetylene gas and helped his father develop a new process for the manufacture of calcium carbide – felt a great degree of debt to the University of North Carolina, for his successes in life were so closely tied to his education in Chapel Hill.

Consequently, Morehead met with University President Frank Porter Graham in 1938 to find a gift that could express his gratitude to the University and open the minds of young North Carolinians to science.

Since the planetarium opened in 1949, millions of North Carolina students, teachers, families, and visitors from around the world have benefitted from Morehead science programs.

Thank Your Lucky Stars

For 16 years, Chapel Hill, NC, was a secret space town. At Morehead Planetarium and Science Center, 62 NASA astronauts, including the first to walk on the moon, trained in celestial navigation to ensure they could return safely to Earth. Their star knowledge even proved critical when Apollo 12’s systems were knocked out by lightning.

PBS North Carolina’s Best of Our State

John Motley Morehead III (1870-1965) graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1891. During his lifetime, he was most widely known as a successful businessman and chemist due to his role in the founding of the Union Carbide Corporation.

Morehead was also politically active as mayor of Rye, New York and U.S. ambassador to Sweden.

In addition to his commercial and political successes, he became a well-known philanthropist and gave generously to his alma mater. His gifts to UNC-Chapel Hill include the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower, the Morehead Planetarium and the Morehead Scholarships Program. The Morehead Scholarships are regarded as the University’s most prestigious undergraduate scholarships.

(Source: The Morehead Foundation)

When first opened in 1949 after seventeen months of construction, Morehead Planetarium was unprecedented. The first planetarium in the South, it was only the eighth to be built in the United States. Designed by the same architects who planned the Jefferson Memorial, the cost of its construction, $3 million, made it the most expensive building ever built in North Carolina at the time. The same construction (not including the 1972 addition) in today’s dollars would be nearly $30 million.

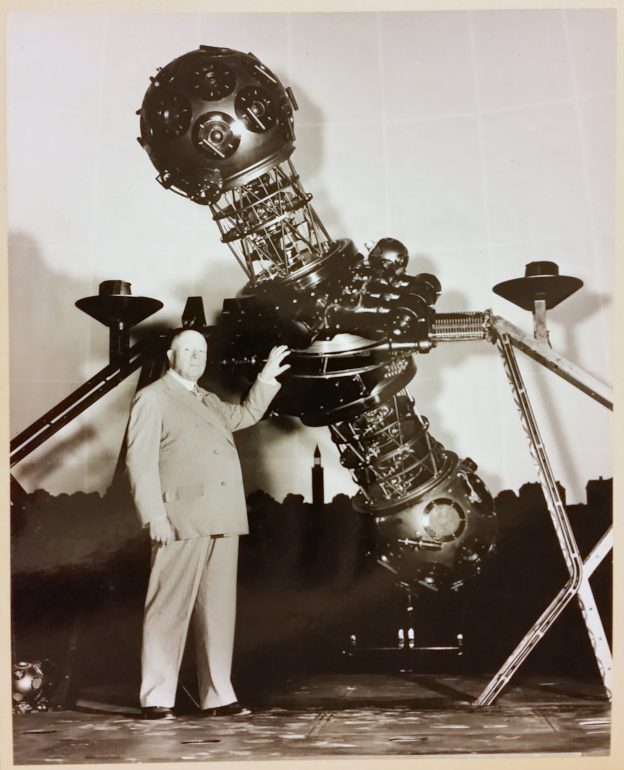

Since Zeiss – the German firm that produced planetarium projectors – had lost most of its factories during World War II, there were very few projectors available at the time. Morehead had to travel to Sweden – where he had previously served as American ambassador – to purchase a Zeiss Model II to serve as the heart of North Carolina’s new planetarium.

Morehead Planetarium was officially dedicated during a ceremony held on May 10, 1949 and attracted some of the North Carolina’s most prominent citizens. U.S. Senator Frank Porter Graham, N.C. Governor Kerr Scott, Acting University President William Carmichael, University Chancellor Robert House, and John Motley Morehead III as well as other members of his family attended the ceremony. Following the dedication, assembled dignitaries viewed the Planetarium’s first show, “Let There Be Light,” narrated by Planetarium Director Roy K. Marshall.

While “Let There Be Light” was the Planetarium’s first show, it would be followed later in 1949 by another show seen perhaps by more Morehead Planetarium and Science Center visitors than any other show to date: “Star of Bethlehem.” This planetarium show was designed to take full advantage of Zeiss projection technology and was revised several times (its final revision was in 2002) before its retirement when Morehead’s Zeiss VI star projector was decommissioned and removed in spring 2011.

The building that Morehead constructed under the counsel of Harlow Shapley wasn’t just another staid lecture hall but was rather a means of projecting science education to a wider audience — one out beyond the stone walls of the University.

Planetariums were seen as a powerful tool for education. In 1925, Elis Stromgren, director of Copenhagen Observatory, lauded, “Never has a means of entertainment been provided which is so instructive as this, never one which is so fascinating, never one which has such general appeal. It is a school, a theater, a cinema in one; a schoolroom under the vault of heaven, a drama with the celestial bodies as actors.”

Ten years after opening, Morehead Planetarium was called to serve not only the people of North Carolina, but also the nation’s burgeoning space program. Astronauts needed training in celestial navigation to keep their spacecraft on course and to ensure that they would be able to pilot their spacecraft if navigational systems failed

Between 1960 and 1975, nearly every astronaut who participated in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz programs trained at Morehead. Several astronauts who later flew on the space shuttle were also involved in this training. When the need for such training ended in 1975, long-time Planetarium Director Tony Jenzano could once claim that, “Carolina is the only university in the country, in fact the world, that can claim all the astronauts as alumni.”

Constructing the special equipment for each mission’s training often tested the ingenuity of the Planetarium’s staff. One special projector for the Apollo trainings had to be put together from old car wax cans fitted with miniature light bulbs. The training device used for the Gemini missions was constructed from plywood, cloth, foam rubber and paper mounted on two barber’s chairs. Using this device, astronauts could control the movement of the star-field to simulate pitch and roll while technicians moved their chairs to simulate yaw (side-to-side movement).

More than once, the training that astronauts received at Morehead saved lives. After automated navigational controls failed following a loss of electricity on the Mercury-Atlas 9 mission, Gordon Cooper had to use the stars to guide his reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. His splashdown eventually proved to be the most accurate in mission history.

When the rocket launching Apollo 12 into space was hit by lightning during take-off, astronauts had to reset their navigational equipment by sighting key stars.

The Apollo 13 mission is likely the most famous instance in which Morehead training proved critical for the space program. After an onboard explosion knocked out navigation systems, a resulting debris field also made it impossible for astronauts to accurately see the surrounding stars. When the debris cleared just before reentry, astronauts were finally able to verify that they were on the correct heading for their return.

Twenty-five years after the safe conclusion of the mission, lessons learned at Morehead were still being passed on to others. In 1995, mission astronaut James Lovell – who was advising the producers of the film “Apollo 13” – wrote to former Planetarium Director Tony Jenzano: “It has been a long time since those days at Morehead Planetarium when you taught me about the stars. I thought I would let you know that your training sank in and 25 years later I was teaching Tom Hanks about the stars.”

Special Note: Griffith Observatory’s Samuel Oschin Planetarium in Los Angeles, CA trained twenty-six astronauts between 1967 and 1972. This overlap with Morehead Planetarium’s later training was partly in service of astronauts who had to be in California a lot while the Apollo command module was being redesigned. Much later, the Burke Baker Planetarium in Houston trained astronauts from roughly 1981 to 1995 in service of the space shuttle program.

Learn about the astronauts who trained at Morehead and the missions they flew here.

Many more people than James Lovell and his fellow astronauts have learned about the stars at Morehead Planetarium. By Morehead’s 50th anniversary in 1999, more than five million spectators – half of them schoolchildren – had visited its Star Theater to learn about the cosmos. Over the past half-century, these five million spectators have all benefited from ongoing updates to the planetarium’s facilities.

Planetarium Director Tony Jenzano, who put together the planetarium’s original Zeiss II star projector, signed off on the delivery of a new Zeiss VI projector in 1969. The planetarium replaced the Zeiss II star projector that Morehead had purchased in Sweden with a Zeiss VI. The Model VI provided a clearer star field, along with improved operational controls and features. Neil Armstrong – the first man to walk on the Moon – also has the distinction of being the first astronaut to train with the Model VI. The Zeiss VI remained in use until April 2011.

In 1973, John Motley Morehead’s full vision for his building was realized when the building’s East Wing opened. The addition included the Morehead Observatory, which is fitted with a 24-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope and is operated by UNC-Chapel Hill’s department of physics and astronomy. This observatory is open, upon reservation, for the public each Friday night during the academic year.

In 1984, Morehead became one of the first planetariums to utilize computer automation for its programs. Before automation, each feature of a planetarium show was set into motion by a technician following a cue by the narrator. With its new capacity for automation, the planetarium expanded its ability to present more complex shows. See the full Planetarium timeline here.

In 2000, John Motley Morehead’s gift to his state and his alma mater was rechristened Morehead Planetarium and Science Center to reflect an expanded mission.

Morehead’s expanded mission still involves being a gateway to the stars, but further includes being a gateway to all the sciences, exposing audiences to fields like genetics, virtual reality, concussion research, and nanotechnology.

“While we are entering a new era at the Morehead Center, we are committed to the original vision of our benefactor, John Motley Morehead III – to educate and inspire our visitors about the wonders of science,” Morehead Director Holden Thorp (2001-2005) said.

In May 2003, the Morehead Center made the first step towards fulfilling its new mission with the debut of the film “DNA: The Secret of Life,” which the Center produced in collaboration with U.K.-based filmmakers, Windfall Films, and James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA.

In 2006, Dr. Todd Boyette became Morehead’s sixth director and continued the venerable institution’s expansion. In the same year, the DESTINY Traveling Science program joined the Morehead family to support the organization’s outreach efforts across the state.

Even while expanding into new disciplines, Morehead has also stayed to true to its roots as a leading planetarium. With the assistance of a major gift from GSK, Morehead converted to fulldome digital technology in 2010 and renamed the theater in GSK’s honor. The transition to digital technology also ushered in a new era for show production. Morehead now produces fulldome shows on a regular basis, ones that can be shown in its GlaxoSmithKline Fulldome Theater, in Morehead’s portable planetarium, and in planetariums worldwide. Thanks to international distribution agreements, Morehead shows are now showing in theaters in more than a dozen countries.

Morehead also founded the North Carolina Science Festival in 2010, making it the first statewide celebration of science in the country. Morehead produces the Festival each spring in collaboration with hundreds of statewide partners.